JBL_L300 custom all original speaker drivers

Martin Logan_SL3 new low price $1150.00

Infinity CS3009

DYN AUDIO

DYN Audio Sub

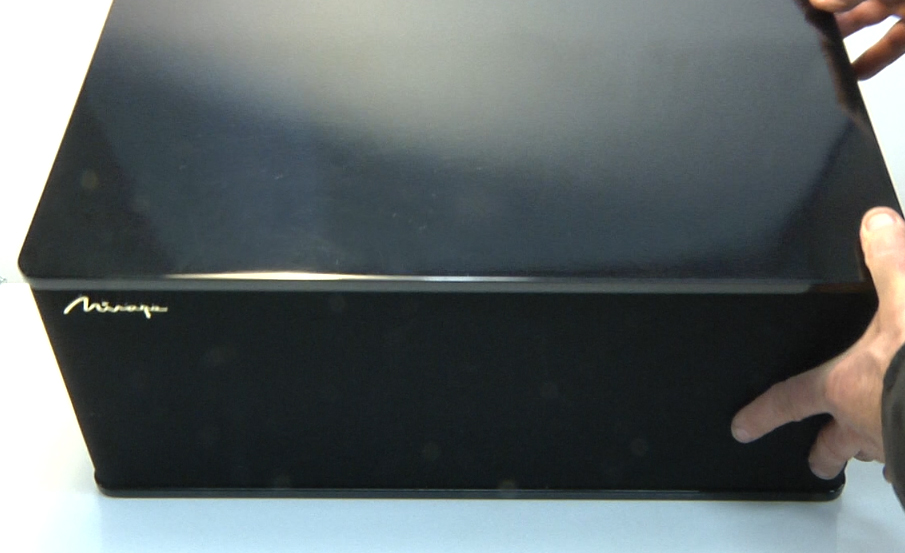

Mirage Speaker System

Mirage Sub $650.00

15 SUB no name $60.00

BOWERS & WILKINS DM602 S2 BOOKSHELF SPEAKERS B&W British Audiophile $200.00

POLK RTi-8 Speakers

DYN Audio Stainless Steel Stands $650.00

Wireless Headphone IR for stage event venue

The 1970s heralded a golden age of audio equipment. Solid state amplifiers established themselves as affordable high-fidelity equipment, and while many prefer valve amplifiers for their warmer sound and higher dynamic range; solid state should not be ruled out when they were designed correctly with the best componets.

A decent vintage amp and classic speakers are bound to provide much more bounce, joy and volume than a similarly priced new pair of new speakers costing 5 time more in price.

Klipschorn

The Klipschorn is the only speaker that has been in continuous production for over 60 years. But that’s not why it makes the list. The Klipschorn is a landmark product due to its folded horn design. Paul Klipsch, inventor and entrepreneur, patented the idea of assembling chambers and passageways for a bass driver’s sound waves to gradually expand as they travel out to the opening. The sound is mechanically amplified by the expanding “folds” in the passageway of the horn. (Without this, a low-frequency horn would be the size of a full room.) In 1946, the first 20 Klipsch loudspeakers were assembled in a tin shack in Hope, Arkansas. The base horn design has never been improved—it was perfect from day one. Klipsch’s four principles of sound reproduction are: efficiency, flat frequency response, controlled directivity, and dynamic range. A Klipschorn provides a detailed wall of sound that emanates from the corner of a room. It was the first “absolute sound.” Imagine the sound of a windup Victrola being replaced overnight by the sound of unamplified live instruments in space. Most amazing is that you can buy it today. That’s 60 years of advancement in one moment. Peter Breuninger

MBL 101 E

In the history of high-end audio, there have been a number of fascinating and genuinely innovative drivers—Alan Hill’s plasma tweeter and Lincoln Walsh’s “transmission-line” cone, for examples. Not all of them caught on—for good reasons (the joke about the Walsh driver used to be that it took 200W to get it to make sound and 201W to blow it up, while the Hill produced enough ozone to choke a horse). Wolfgang Meletzsky’s omnidirectional “Radialstrahler”—a truly ingenious pumpkin-shaped contraption constructed of aluminum/magnesium “petals” that flex in and out in response to an audio signal (like the pleats of an accordion), producing near-equal sound pressure throughout 360 degrees (rather, dare I say it, like a pulsating, er, pumpkin)—is certainly a brilliant concept and happily it doesn’t blow up or poison the air. What it does do is produce the most enveloping soundstage this side of a surround system, absolutely thrilling large-scale dynamics, and timbres that are very true-to-life (in frequency response, the MBL is an exceedingly flat-measuring loudspeaker). Though omnis aren’t as commonplace as they once were back in the day, the sui generis 101s set a standard of excellence and sheer lifelike excitement that has kept them the foremost omnidirectional speakers for more than thirty years. Jonathan Valin

Advent

Not very long ago, a long-time audio buddy gave me a chance to hear his Double Advent setup (and in his garage!). The experience in a sense, just about took my breath away: The speakers, even in that primitive setting, were magnificent! They remained as uncolored and neutral as ever, exceeding too many of today’s so-called “super” systems. I had, if the truth be told, forgotten (audibly) just how very special this doubling up [stacking a pair atop another pair] of Henry Kloss’ last great speaker was and remains. Wished I had had the sense to hold on to the pair I bought (back when, actually in 1972, just before I started Issue One of this rag). The Advents weren’t then entirely trouble-free thanks to mechanical problems with the original tweeters. Seen in today’s light, aside from an airy top end, the only thing missing was its ability to recreate a wide and dimensional soundstage. If you can grab a pair in good condition, and they are out there, be smarter than me. Harry Pearson

Infinity IRS V

This was the last version of the original Infinity Reference System, and, by any measure, the best, standing second to none in frequency range, in a top-to-bottom coherency that had eluded designer Arnie Nudell in the earlier three versions (yes, three, there was no IV), and in an overall faithfulness to the real thing that exceeded Nudell’s best previous efforts. The EMIT tweeters had been considerably updated (so that there was less grain, less artificial brightness, and a sound just a few steps below that of Jim Winey’s Magnepan true ribbon); the EMIT and the ENIN midranges (a replacement for the Series One’s bipolar ribbons) were both now planar “ribbons”; and the non-Watkins graphite-fiber woofers, all 12 of them, were now powered by a 2000-watt amp (up from 1500 in the Series III). What this, finally, accomplished, along with a few other mods, was a seamless sonic transition between the bass and the upper drivers—a first in a Nudell product. A dream realized and a dream for this listener. Harry Pearson

Magnepan 1-U/1-D

Of all the loudspeakers I’ve heard in a lifetime of listening, the large, three-panel Maggie 1-Us—Magnepan’s first widely marketed planar-magnetic speaker—remain the most memorable. I’ve told the story several times before of how I originally (and unwittingly) auditioned these speakers in the early 70s and—not knowing what a Magneplanar was back then—assumed that the real grand piano ensconced behind the “screens” at the far end of the listening room was making music when, in fact (and of course), it was the Maggies that were doing same. I’ve never again been fooled that completely by a loudspeaker because nothing I’ve heard since then has sounded that much more like the real thing than the Maggie 1-Us did at the dawn of the high-end era. As HP put it in his ground-breaking TAS review: “The Magneplanars are…[a] ‘classic’…a speaker that is and will be a standard by which and to which others will be compared.” And so they were, and so they still are, in certain key respects (such as midrange realism and mid-to-upper bass resolution, scale, and slam), to me. Jonathan Valin

Rogers/BBC LS3/5a

The LS3/5a was a BBC design, licensable to any manufacturer. But it was the Rogers version in particular that swept the USA in the late 1970s. This small two-way (7.5" x 12" x 6.25") offered startlingly realistic vocal reproduction and a remarkably expansive and “boxless” sound picture. With its essentially neutral midband but upper bass bump and slightly projected treble, it was not entirely flat, and it had no deep bass. But for a whole generation of listeners, it redefined the possible for small speakers. Some other, larger BBC-influenced designs—the Spendor BC1 first and the Spendor SP1 and SP1/2 and Harbeth Monitor 40 later on—were better speakers overall. But none quite seized the imagination of the U.S. audio public as did the little LS3/5a. With an updated version still in production today, the LS3/5a has stood the test of time as few other speakers have. Robert E. Greene

Acoustic Research AR3a

Edgar Villchur invented the acoustic-suspension loudspeaker. He founded the Acoustic Research Company with Henry Kloss and began production of the AR1 in 1955. The acoustic suspension principle was elegantly simple; Villchur mounted a long-throw 12" woofer in a sealed box, using the air trapped inside the box as the spring to launch the woofer’s cone. His design so reduced the size of the cabinet that you could place it on a bookshelf, making it an instant sensation.In 1958 Villchur demonstrated a new 3-way version, the AR3, with live vs. recorded events where the musicians would stop playing the notes but continue to “pretend” to play as the ARs were switched on. Suddenly, the musicians would stop and freeze while the music continued. Jaws would drop; everyone was fooled—it made newspaper headlines! At its peak the AR3a captured 33% of the high-fidelity loudspeaker market. The Smithsonian Institution has placed the AR3 on permanent display in The National Museum of American History. Peter Breuninger

Quad ESL-57

There was of course never any such moniker as “ESL-57,” except in retrospect, to distinguish it from its distinguished successor the ESL-63. Designed by the legendary Peter Walker and actually introduced in 1956, it was called simply the Quad ESL, but soon became known as “Walker’s little wonder.” Little wonder: For top-to-bottom clarity, coherence, transparency, resolution, openness, naturalness, and a disappearing act that still inspires awe, the ESL established and remains to this day (even though production ceased over a quarter century ago) a reference standard among countless designers and reviewers (including the undersigned) across the globe. Despite undeniable limitations—inability to play very loud, lack of deep bass, quite directional highs—it tops virtually every list of the best, the greatest, the most significant—supply your own category—audio products ever made. Why? Because at the dawn of the stereo era this “little” wonder demonstrated what was possible in most of the essential areas of speaker performance so validly that from a certain point of view the subsequent history of speaker design has been catch-up. Paul Seydor

The 1970s heralded a golden age of audio equipment. Solid state amplifiers established themselves as affordable high-fidelity equipment, and while many prefer valve amplifiers for their warmer sound and higher dynamic range; solid state should not be ruled out when they were designed correctly with the best componets.

A decent vintage amp and classic speakers are bound to provide much more bounce, joy and volume than a similarly priced new pair of new speakers costing 5 time more in price.

Klipschorn

The Klipschorn is the only speaker that has been in continuous production for over 60 years. But that’s not why it makes the list. The Klipschorn is a landmark product due to its folded horn design. Paul Klipsch, inventor and entrepreneur, patented the idea of assembling chambers and passageways for a bass driver’s sound waves to gradually expand as they travel out to the opening. The sound is mechanically amplified by the expanding “folds” in the passageway of the horn. (Without this, a low-frequency horn would be the size of a full room.) In 1946, the first 20 Klipsch loudspeakers were assembled in a tin shack in Hope, Arkansas. The base horn design has never been improved—it was perfect from day one. Klipsch’s four principles of sound reproduction are: efficiency, flat frequency response, controlled directivity, and dynamic range. A Klipschorn provides a detailed wall of sound that emanates from the corner of a room. It was the first “absolute sound.” Imagine the sound of a windup Victrola being replaced overnight by the sound of unamplified live instruments in space. Most amazing is that you can buy it today. That’s 60 years of advancement in one moment. Peter Breuninger

MBL 101 E

In the history of high-end audio, there have been a number of fascinating and genuinely innovative drivers—Alan Hill’s plasma tweeter and Lincoln Walsh’s “transmission-line” cone, for examples. Not all of them caught on—for good reasons (the joke about the Walsh driver used to be that it took 200W to get it to make sound and 201W to blow it up, while the Hill produced enough ozone to choke a horse). Wolfgang Meletzsky’s omnidirectional “Radialstrahler”—a truly ingenious pumpkin-shaped contraption constructed of aluminum/magnesium “petals” that flex in and out in response to an audio signal (like the pleats of an accordion), producing near-equal sound pressure throughout 360 degrees (rather, dare I say it, like a pulsating, er, pumpkin)—is certainly a brilliant concept and happily it doesn’t blow up or poison the air. What it does do is produce the most enveloping soundstage this side of a surround system, absolutely thrilling large-scale dynamics, and timbres that are very true-to-life (in frequency response, the MBL is an exceedingly flat-measuring loudspeaker). Though omnis aren’t as commonplace as they once were back in the day, the sui generis 101s set a standard of excellence and sheer lifelike excitement that has kept them the foremost omnidirectional speakers for more than thirty years. Jonathan Valin

Advent

Not very long ago, a long-time audio buddy gave me a chance to hear his Double Advent setup (and in his garage!). The experience in a sense, just about took my breath away: The speakers, even in that primitive setting, were magnificent! They remained as uncolored and neutral as ever, exceeding too many of today’s so-called “super” systems. I had, if the truth be told, forgotten (audibly) just how very special this doubling up [stacking a pair atop another pair] of Henry Kloss’ last great speaker was and remains. Wished I had had the sense to hold on to the pair I bought (back when, actually in 1972, just before I started Issue One of this rag). The Advents weren’t then entirely trouble-free thanks to mechanical problems with the original tweeters. Seen in today’s light, aside from an airy top end, the only thing missing was its ability to recreate a wide and dimensional soundstage. If you can grab a pair in good condition, and they are out there, be smarter than me. Harry Pearson

Infinity IRS V

This was the last version of the original Infinity Reference System, and, by any measure, the best, standing second to none in frequency range, in a top-to-bottom coherency that had eluded designer Arnie Nudell in the earlier three versions (yes, three, there was no IV), and in an overall faithfulness to the real thing that exceeded Nudell’s best previous efforts. The EMIT tweeters had been considerably updated (so that there was less grain, less artificial brightness, and a sound just a few steps below that of Jim Winey’s Magnepan true ribbon); the EMIT and the ENIN midranges (a replacement for the Series One’s bipolar ribbons) were both now planar “ribbons”; and the non-Watkins graphite-fiber woofers, all 12 of them, were now powered by a 2000-watt amp (up from 1500 in the Series III). What this, finally, accomplished, along with a few other mods, was a seamless sonic transition between the bass and the upper drivers—a first in a Nudell product. A dream realized and a dream for this listener. Harry Pearson

Magnepan 1-U/1-D

Of all the loudspeakers I’ve heard in a lifetime of listening, the large, three-panel Maggie 1-Us—Magnepan’s first widely marketed planar-magnetic speaker—remain the most memorable. I’ve told the story several times before of how I originally (and unwittingly) auditioned these speakers in the early 70s and—not knowing what a Magneplanar was back then—assumed that the real grand piano ensconced behind the “screens” at the far end of the listening room was making music when, in fact (and of course), it was the Maggies that were doing same. I’ve never again been fooled that completely by a loudspeaker because nothing I’ve heard since then has sounded that much more like the real thing than the Maggie 1-Us did at the dawn of the high-end era. As HP put it in his ground-breaking TAS review: “The Magneplanars are…[a] ‘classic’…a speaker that is and will be a standard by which and to which others will be compared.” And so they were, and so they still are, in certain key respects (such as midrange realism and mid-to-upper bass resolution, scale, and slam), to me. Jonathan Valin

Rogers/BBC LS3/5a

The LS3/5a was a BBC design, licensable to any manufacturer. But it was the Rogers version in particular that swept the USA in the late 1970s. This small two-way (7.5" x 12" x 6.25") offered startlingly realistic vocal reproduction and a remarkably expansive and “boxless” sound picture. With its essentially neutral midband but upper bass bump and slightly projected treble, it was not entirely flat, and it had no deep bass. But for a whole generation of listeners, it redefined the possible for small speakers. Some other, larger BBC-influenced designs—the Spendor BC1 first and the Spendor SP1 and SP1/2 and Harbeth Monitor 40 later on—were better speakers overall. But none quite seized the imagination of the U.S. audio public as did the little LS3/5a. With an updated version still in production today, the LS3/5a has stood the test of time as few other speakers have. Robert E. Greene

Acoustic Research AR3a

Edgar Villchur invented the acoustic-suspension loudspeaker. He founded the Acoustic Research Company with Henry Kloss and began production of the AR1 in 1955. The acoustic suspension principle was elegantly simple; Villchur mounted a long-throw 12" woofer in a sealed box, using the air trapped inside the box as the spring to launch the woofer’s cone. His design so reduced the size of the cabinet that you could place it on a bookshelf, making it an instant sensation.In 1958 Villchur demonstrated a new 3-way version, the AR3, with live vs. recorded events where the musicians would stop playing the notes but continue to “pretend” to play as the ARs were switched on. Suddenly, the musicians would stop and freeze while the music continued. Jaws would drop; everyone was fooled—it made newspaper headlines! At its peak the AR3a captured 33% of the high-fidelity loudspeaker market. The Smithsonian Institution has placed the AR3 on permanent display in The National Museum of American History. Peter Breuninger

Quad ESL-57

There was of course never any such moniker as “ESL-57,” except in retrospect, to distinguish it from its distinguished successor the ESL-63. Designed by the legendary Peter Walker and actually introduced in 1956, it was called simply the Quad ESL, but soon became known as “Walker’s little wonder.” Little wonder: For top-to-bottom clarity, coherence, transparency, resolution, openness, naturalness, and a disappearing act that still inspires awe, the ESL established and remains to this day (even though production ceased over a quarter century ago) a reference standard among countless designers and reviewers (including the undersigned) across the globe. Despite undeniable limitations—inability to play very loud, lack of deep bass, quite directional highs—it tops virtually every list of the best, the greatest, the most significant—supply your own category—audio products ever made. Why? Because at the dawn of the stereo era this “little” wonder demonstrated what was possible in most of the essential areas of speaker performance so validly that from a certain point of view the subsequent history of speaker design has been catch-up. Paul Seydor